Understanding Somatic & Germline Mutations

Feb 3, 2026

Share article

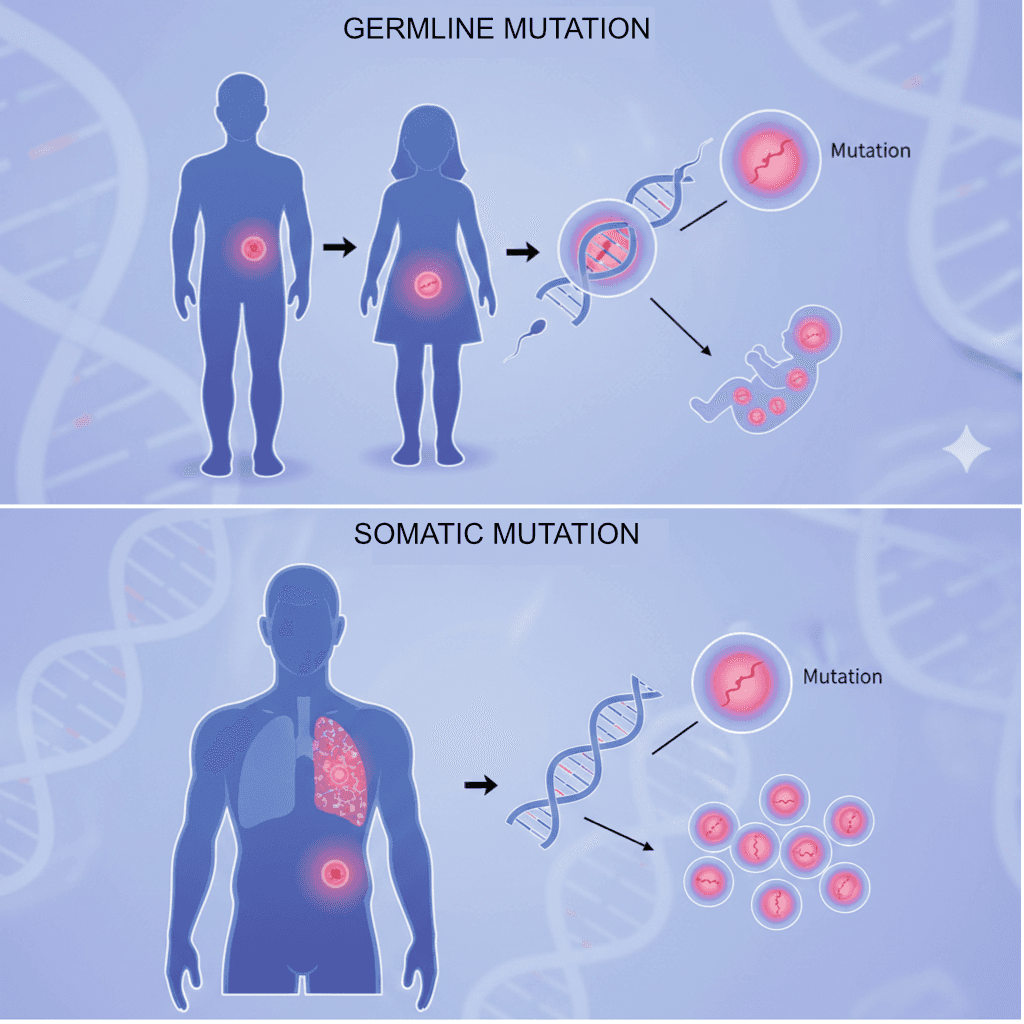

Germline and somatic mutations play distinct roles in disease, especially cancer. This article explores their molecular differences, impact on inheritance and progression, and how inherited predispositions and acquired mutations together influence tumor development and treatment strategies.

Understanding the distinction between germline and somatic mutations is fundamental to understanding disease mechanisms, particularly in cancer biology.

This educational resource provides an exploration of both mutation types, their molecular mechanisms, and their relevance in many diseases including cancers, where the interplay between inherited predisposition and acquired mutations shapes tumor development and treatment response.

Germline Mutations

Heritable changes in reproductive cells

Definition & Characteristics

Germline mutations are genetic changes that occur in the germ cells (eggs and sperm) or are present in the fertilized egg. These mutations are incorporated into every cell of the developing organism and can be transmitted to future generations.

These hereditary alterations form the basis of inherited genetic disorders and familial cancer syndromes. When a germline mutation is present, every cell in the body carries that alteration, making the individual susceptible to associated conditions throughout their lifetime.

Take away

Present in all cells of the body (constitutional)

Inherited from parents or arise de novo in gametes

Transmissible to offspring (50% chance per child)

Detectable through standard genetic testing of any tissue

Common Diseases Caused by Germline Mutations

Single-Gene Disorders:

Cystic Fibrosis: Affects lungs, pancreas, digestive system (CFTR gene).

Sickle Cell Anemia: Blood disorder (HBB gene).

Huntington's Disease: Progressive neurological disorder (HTT gene).

Tay-Sachs Disease: Fatal neurological disorder (HEXA gene).

Color Blindness: Vision defect (OPN1LW, OPN1MW genes).

Syndromic Disorders (RASopathies):

Noonan Syndrome, NF1, Costello Syndrome: Affect heart, face, skin, neurodevelopment (RAS/MAPK pathway genes).

Hereditary Cancer Syndromes:

BRCA1/2-associated cancers: Breast, ovarian, prostate, pancreatic (BRCA1, BRCA2 genes).

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia (MEN): Tumors in endocrine glands (MEN1, MEN4 genes).

Hematologic Malignancies Predisposition:

Leukemia/AML/ALL: Predisposition due to mutations in TP53, RUNX1, GATA2.

Clinical Implications

Diagnosis & Counseling: Genetic testing identifies carriers, informs family planning, and guides risk assessment.

Prognosis: Germline mutations can define disease severity and progression.

Treatment:

Targeted Therapies: PARP inhibitors for BRCA-related cancers.

Early Intervention: Regular screening for tumors (e.g., pituitary adenomas in AIP mutation carriers).

Symptom Management: Specific treatments for conditions like cystic fibrosis or Huntington's.

Pharmacogenomics: Can influence drug response (e.g., Ivacaftor for CF).

Germline mutations are heritable changes in reproductive cells, while somatic mutations are acquired alterations in non-reproductive cells.

Somatic Mutations

Acquired changes in non-reproductive cells

Definition & Characteristics

Somatic mutations are genetic alterations that occur in any cell of the body except germ cells (sperm and eggs). These mutations arise after conception and accumulate throughout an individual's lifetime due to various endogenous and exogenous factors.

Unlike germline mutations, somatic mutations are not inherited by offspring. They are confined to the individual in whom they originate and can affect any tissue or organ system. They arise during DNA replication or from environmental damage.

Take away

Present only in derived cell lineages (clonal)

Not transmitted to future generations

Accumulate with age and environmental exposure

Common Causes

Replication errors

UV radiation

Chemical carcinogens

Oxidative stress

Viral integration

Clinical Significance

Somatic mutations are the primary drivers of cancer development. The accumulation of mutations in key oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes leads to uncontrolled cell proliferation and tumor formation. Importantly, the tumor mutational burden (TMB) - the total number of somatic mutations in a tumor - has emerged as a biomarker for immunotherapy response.

Modern sequencing technologies enable comprehensive profiling of somatic mutations, allowing for precision oncology approaches where treatment is tailored based on the specific genetic alterations present in an individual's tumor.

Genetic Testing & Counseling

Germline genetic testing has become an integral component of cancer risk assessment. Identifying pathogenic germline variants enables cascade testing of family members, allowing for early detection strategies, prophylactic interventions, and informed reproductive decisions.

Genetic counseling is essential when dealing with germline findings, as results have implications beyond the individual patient, affecting siblings, children, and extended family members who may carry the same inherited risk.

Key Differences at a Glance

Characteristic | Somatic | Germline |

Cell Type Affected | Any cell except germ cells | Egg or sperm cells |

Inheritance | Not heritable | Passed to offspring |

Distribution in Body | Clonal (limited tissues) | All cells (constitutional) |

When Acquired | After conception (lifetime) | Before/at conception |

Detection Method | Tumor sequencing | Blood/saliva testing |

Clinical Action | Targeted therapy selection | Family screening, prevention |

Implications in Cancer Biology

Understanding the interplay between somatic and germline mutations is crucial for modern oncology practice and precision medicine.

Somatic Mutations in Tumors

Cancer is fundamentally a disease of somatic mutations. The step-wise accumulation of driver mutations in oncogenes (e.g., KRAS, EGFR, BRAF) and tumor suppressors (e.g., TP53, RB1, PTEN) drives malignant transformation.

Therapeutic Implications:

Targeted therapies: EGFR inhibitors, BRAF/MEK inhibitors

Immunotherapy: High TMB predicts checkpoint inhibitor response

Resistance monitoring: Tracking clonal evolution

Germline Predisposition

Approximately 5-10% of cancers arise in the context of inherited germline mutations. These hereditary cancer syndromes often present with earlier onset, multiple primary tumors, and distinct pathological features.

Clinical Management:

PARP inhibitors: Effective in BRCA1/2-mutated tumors

Enhanced surveillance: MRI screening, colonoscopy protocols

Prophylactic surgery: Risk-reducing mastectomy, oophorectomy

Integrated Genomic Assessment

Modern oncology practice increasingly recognizes the importance of paired tumor-normal sequencing, analyzing both the tumor (for somatic mutations) and normal tissue (to identify germline variants).

This approach enables:

Accurate Variant Classification: Distinguishing somatic from germline origin

Homologous Recombination Deficiency: Identifying BRCA-ness for PARP inhibitor eligibility

Incidental Germline Findings: Discovering unsuspected hereditary risk

Ressources:

Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458(7239):719–724.

Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339(6127):1546–1558.

Hanahan D. Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(1):31–46.

Knudson AG Jr. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68(4):820–823.

Rahman N. Realizing the promise of cancer predisposition genes. Nature. 2014;505(7483):302–308.

Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, et al. Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2402–2416.

Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(6):523–533.

ACMG Board of Directors. ACMG recommendations for reporting secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing (update). Genet Med. 2015;17(1):68–69.

Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348(6230):124–128.

Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN, et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51(2):202–206.

Lord CJ, Ashworth A. BRCAness revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(2):110–120.

Meric-Bernstam F, Brusco L, Daniels M, et al. Feasibility of large-scale genomic testing to facilitate enrollment onto genomically matched clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2753–2762.

Mandelker D, Zhang L, Kemel Y, et al. Navigating highly penetrant cancer susceptibility genes in tumor-only sequencing. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017:1–12.

Schrader KA, Cheng DT, Joseph V, et al. Germline variants in targeted tumor sequencing using matched normal DNA. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(1):104–111.

somatic mutations

germline mutation

oncology

Share this article :

Share